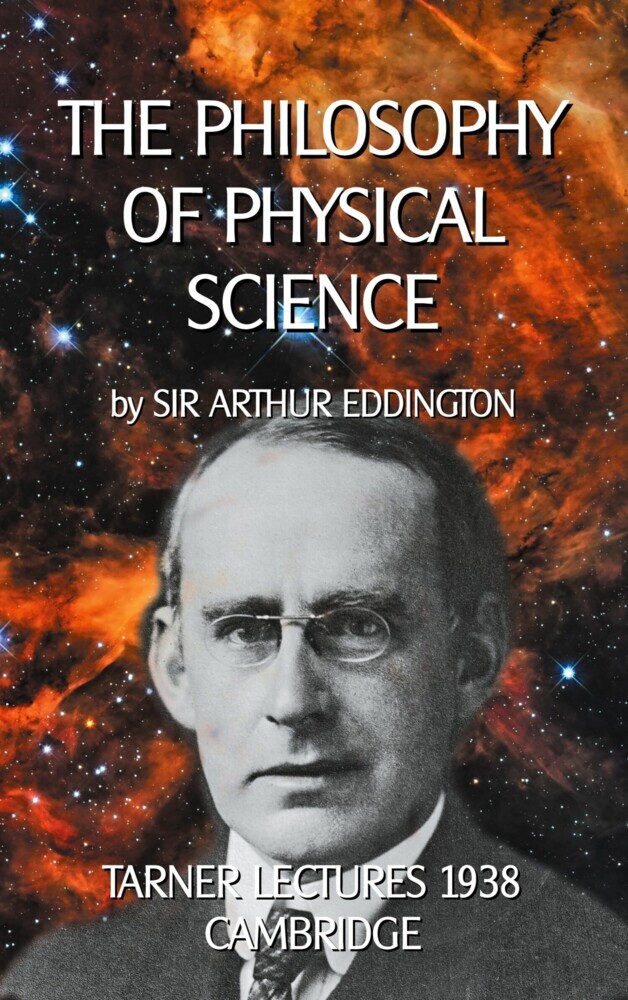

The Philosophy of Physical Science

TARNER LECTURES 1938 - CAMBRIDGE

EPUB (mit DRM) sofort downloaden

Downloads sind nur in Italien möglich!

Produktdetails

- Verlag

- Books on Demand

- Erschienen

- 2019

- Sprache

- English

- Seiten

- 196

- Infos

- 196 Seiten

- ISBN

- 978-3-7494-1379-9

Kurztext / Annotation

It is often said that there is no "philosophy of science", but only the philosophies of certain scientists. But in so far as we recognize an authoritative body of opinion which decides what is and what is not accepted as present-day physics, there is an ascertainable present-day philosophy of physical science. It is the philosophy to which those who follow the accepted practice of science stand committed by their practice. This book contains the substance of the course of lectures which the author Eddington delivered as Tarner Lecturer of Trinity College Cambridge in the Easter Term 1938. The lectures have afforded him an opportunity of developing more fully than in his earlier books the principles of philosophic thought associated with the modern advances of physical science.

The English astronomer and mathematician Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington is famous for his work concerning the theory of relativity. He is also well known a philosopher of science and a populariser of science.

Textauszug

CHAPTER II

SELECTIVE SUBJECTIVISM

I

Let us suppose that an ichthyologist is exploring the life of the ocean. He casts a net into the water and brings up a fishy assortment. Surveying his catch, he proceeds in the usual manner of a scientist to systematise what it reveals. He arrives at two generalisations:

(1) No sea-creature is less than two inches long.

(2) All sea-creatures have gills. These are both true of his catch, and he assumes tentatively that they will remain true however often he repeats it.

In applying this analogy, the catch stands for the body of knowledge which constitutes physical science, and the net for the sensory and intellectual equipment which we use in obtaining it. The casting of the net corresponds to observation; for knowledge which has not been or could not be obtained by observation is not admitted into physical science.

An onlooker may object that the first generalization is wrong. "There are plenty of sea-creatures under two inches long, only your net is not adapted to catch them." The ichthyologist dismisses this objection contemptuously. "Anything uncatchable by my net is ipso facto outside the scope of ichthyological knowledge, and is not part of the kingdom of fishes which has been defined as the theme of ichthyological knowledge. In short, what my net can't catch isn't fish." Or-to translate the analogy-"If you are not simply guessing, you are claiming a knowledge of the physical universe discovered in some other way than by the methods of physical science, and admittedly unverifiable by such methods. You are a metaphysician. Bah!"The dispute arises, as many disputes do, because the protagonists are talking about different things. The onlooker has in mind an objective kingdom of fishes. The ichthyologist is not concerned as to whether the fishes he is talking about form an objective or subjective class; the property that matters is that they are catchable. His generalization is perfectly true of the class of creatures he is talking about-a selected class perhaps, but he would not be interested in making generalizations about any other class. Dropping analogy, if we take observation as the basis of physical science, and insist that its assertions must be verifiable by observation, we impose a selective test on the knowledge which is admitted as physical. The selection is subjective, because it depends on the sensory and intellectual equipment which is our means of acquiring observational knowledge. It is to such subjectively-selected knowledge, and to the universe which it is formulated to describe, that the generalizations of physics- the so-called laws of nature-apply.

It is only with the recent development of epistemological methods in physics that we have come to realise the far-reaching effect of this subjective selection of its subject matter. We may at first, like the onlooker, be inclined to think that physics has missed its way, and has not reached the purely objective world which, we take it for granted, it was trying to describe. Its generalisations, if they refer to an objective world, are or may be rendered fallacious through the selection; But that amounts to condemning observationally grounded science as a failure because a purely objective world is not to be reached by observation.

Clearly an abandonment of the observational method of physical science is out of the question. Observationally grounded science has been by no means a failure; though we may have misunderstood the precise nature of its success. Those who are dissatisfied with anything but a purely objective universe may turn to the metaphysicians, who are not cramped by the self-imposed ordinance that every assertion must be capable of submission to observation as the final Court of Appeal. But we, as physicists, shall continue to study the univers

Beschreibung für Leser

Unterstützte Lesegerätegruppen: PC/MAC/eReader/Tablet